Beneath the Floorboards:

Whispers of the Enslaved at Marlpit Hall

Middle School / High School Education Resource

Welcome to Colonial Monmouth!

Marlpit Hall in Middletown, NJ stands today as a window into the 18th century. This c. 1762 home and its residents witnessed many of the most exciting, inspirational, and painful chapters in our history, from the fight for independence to the heartbreak of slavery. Join us as we explore what life was like from a unique perspective; through the lens of the enslaved Marlpit Hall.

Unbroken Chains: Meet the Taylors of Marlpit Hall

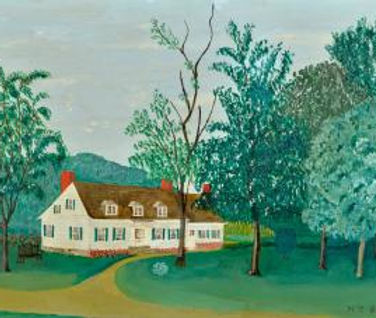

Above, the oldest known image of Marlpit Hall, taken in 1886 from the roof of what is now known as the Taylor-Butler house.

The house known today as Marlpit Hall was constructed around 1762. Edward Taylor purchased the home in 1771, beginning an unbroken chain of Taylor ownership until 1931. There was also an unbroken chain of slave ownership through at least 1832, where men, women and children worked the fields, grist mill, and inside the house to maintain the Taylor lifestyle.

Seeds of Slavery

As early as the 1620s, Dutch slave traders were transporting small numbers of enslaved Africans into the New Netherlands, the territory later known as New York and northern New Jersey. But it was not until New Jersey came under British rule in 1664 that the institution of slavery grew into a cornerstone of colonial society.

Early English provincial law encouraged settlers to maintain enslaved labor. In one of New Jersey's founding documents, The Concession and Agreement of the Lords Proprietors of the Province of Nova Caesarea, white settlers were granted an additional seventy-five acres of land for every enslaved person they brought with them.

Slavery spread quickly in East Jersey. Around 1675, Colonel Lewis Morris expanded his iron works at Tinton Falls in Shrewsbury with the labor of 60 enslaved Africans. His nephew, also Lewis Morris, would become the colonial royal governor of New Jersey. The enslaved labor working at Tinton Manor provided the template for Monmouth County's budding slave society.

Sketch of Tinton Manor, c. 1680

By 1720, most enslaved Africans were brought to New Jersey from West Africa through the port at Perth Amboy. Those who came through the West Indies were seasoned for the slave market in a process that exposed them to new foods, disease, language, and agricultural training. Seasoning was a particularly cruel and enduring practice that claimed the lives of countless enslaved Africans.

They Were There

Click an image to learn about the individual

Tom

Elizabeth

Clarisse

York

Will

Hannah

Ephraim

The Taylor family of Marlpit Hall, like many of prominence and wealth in early Monmouth County, relied on slave labor. From around 1780 to 1830, Marlpit Hall was the primary residence of at least ten enslaved African Americans: York, Tom, MaryAnn, Elizabeth, William, Hannah, Matilda, Clarisse, Ephraim, and George. Four were likely born at Marlpit Hall.

What is a kitchen family?

White families and their enslaved often ate, slept, and worked within very close proximity to one another. Some households referred to enslaved African Americans as their "kitchen family;" a misleading term, given the way these individuals were treated.

An 1818 inventory of Marlpit Hall's upper level kitchen chambers reveals modest provisions for the enslaved: straw beds and bedding, cots, a rocking cradle, and a trundle bed. Wool and linen wheels, as well as a quilting frame, suggest that some women also used this space for spinning and weaving.

The "Kitchen Family"

Community of "Africa" near present day Matawan

Free

Black

Society

I would like to tell you many things...I don't tell all, but I keep it in my heart.

Katy Schenck, 1851

Born into slavery in Freehold

The enslaved protested their condition daily in different ways. Rather than leaving their African heritage behind, they celebrated it - secretly - through religion, food, and music. Some pretended to be sick or did a poor job of their tasks, such as burning meals, breaking tools, or working slowly. Some staged insurrections or destroyed property. Escaping was also a brave act of resistance.

Resistance!!

So...

How Do We Know

What We Know?

The stories of the enslaved at

Marlpit Hall were told using primary source documents and material

culture. Learn how to analyze

and use these tools!

Many Thanks to Our Advisory Panel:

Hank Bitten, Executive Director of the New Jersey Council for the Social Studies

Dr. Wendy Morales, Assistant Superintendent of the Monmouth Ocean Educational Services Committee

Noelle Lorraine Williams, Director of the African American History Program, New Jersey Historical Commission

Upper Elementary Level Resource:

Please visit the companion resource for grades 3-5 here, or find it at monmouthhistory.org/colonial-slavery.

Professional Development, Class Trips or Questions:

To arrange a professional development session or a class trip to our award-winning exhibit, Beneath the Floorboards: Whispers of the Enslaved at Marlpit Hall, please contact Dana at dhowell@monmouthhistory.org