Shore Neighborhoods Support Loyalists

by Michael Adelberg

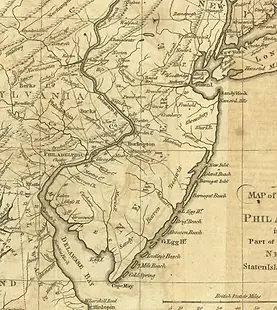

In between privateering villages that supported the Revolution, large stretches of the Jersey shore were thinly-populated and largely disaffected from the Revolution.

- January 1779 -

In 1778, the New Jersey shoreline divided into adversarial camps. On one side, men took to sea to prey on vulnerable British/Loyalist ships, and muster into militia companies that attempted to impose order on locals who were disaffected from the new government. On the other side were “disaffecteds” who resisted militia service and supported Loyalist insurrections since the start of the war. The more violent of these men formed into outlaw gangs often called Pine Robbers. In between the two camps were opportunistic “trimmers,” a reference to trimming sails on a ship based on whichever way the wind was blowing.

Continued Disaffect on the Monmouth Shore

On January 25, 1779, Captain Andrew Brown of the Dover Township militia, stationed at Toms River, wrote about a Pine Robber gang that had the support of people on the shore:

I would hope if any Continental troops should be stationed in Monmouth, you should move it to the commanding officer to station some of them at this place, as it might be advantageous to themselves and very serviceable in having an awe on a set of vagabonds that lurks about here and is too much countenanced by some of the inhabitants.

Prominent Loyalists in New York were well aware of this disaffected population. In early 1779, New Jersey’s last Royal Governor, William Franklin, predicted that the New Jersey shore was "ready to rise" if the British would create a permanent base on the Shrewsbury shore. Similarly, the prominent Loyalist Andrew Elliot wrote about the lumber trade with the New Jersey shore: "The refugees [are] all employed in cutting wood on rebel lands by which they make money and help keep the town [New York] well supplied." A third prominent Loyalist, William Smith, wrote of disaffected on the Monmouth shore: “The people of Monmouth wish it to promote a rising and desertions.” He claimed that 60 would-be Loyalists were recently taken by Continental forces due to a lack of British support (this number is likely exaggerated).

Various incidents illustrate that much of the shore region was disaffected. On November 4, William Burke, wrote the Continental Congress about his privateer, beached near Egg Harbor:

I was cast away in the ship Henry from Boston last Thursday at Brigantine Beach. I landed yesterday to find the majority of people have inclined to plunder. There are no leading men amongst them and I am obliged to keep my own people under arms day & night.

Burke continued, “I have no money and cannot get assistance... the public stores are in danger of being plundered." Burke was seeking help when he wrote this letter. The fate of the Henry is unknown.

That same month, Captain Patrick Ferguson proposed an ambitious one-week raid of New Jersey to Henry Clinton, the commanding British general in New York. Ferguson had spent two weeks around Egg Harbor during October 1778 and had firsthand experience with shore residents. His proposed campaign included attacks on "the piratical town of Barnegat,” “that very rebel coast to Toms River," and "the pirates at Squan Inlet & Shark River.” But Ferguson also expected that his mounted Loyalists would be greeted by shore residents who had “indifference” and “disgust” for the rebel government. Ferguson’s plan was never implemented.

In early 1780, a small Loyalist privateer, manned of Loyalist refugees in New York, made at least two successful trips along the Jersey shore. They embarked in a whaleboat (long rowboat) named Lewistown Revenge with a swivel gun in the bow. The Loyalist New York Gazette & Weekly Mercury reported twice in March on its voyages. It reported in greater detail on the first trip:

They passed Sandy Hook and proceeded to Egg Harbour where they found three privateers ready for sea and a 12 gun schooner laden with lumber. Their number being inadequate for the force collected there, they pretended to be rebels and spent an evening with those who were really such in a most social manner.

The Loyalists then proceeded to Delaware Bay where "they captured a loaded vessel" and a second vessel. They captured and paroled "between fifty and sixty rebel prisoners." One of their prizes was lost at Cape May, the other was taken back to Sandy Hook. A second voyage on the Jersey shore yielded another prize. In order for a rowboat to traverse the Jersey shore twice without attack, the men on the boat must have had allies along the way with fresh water, food, and shelter.

This assertion is supported by an April 7 letter Colonel Samuel Forman to Governor William Livingston in which Forman, commanding the militia from present-day Ocean County, complained about resurgent disaffection. “The lower part of the county is in continual possession of the enemy.” Forman further wrote that Loyalists “march below in security in companies of 40 or 60 in number.” Many of the shore’s few patriots were captured. He concluded: “The county is now in a worse state than it was in the year 1776 when they layed [sic] down arms."

A May 1780 petition from the leaders of Toms River offered the same sentiments:

The enemies of the United States, as well as those without the lines and those more secret ones within, do carry on a clandestine trade contrary to the laws of this State & to the great detriment of the present cause and to the inhabitants of Toms River, [who] have been frequently threatened to be plundered & their houses laid to ashes; the militia not being very numerous and hard to be called together.

The petitioners called for the state to finance a 30-man state troop guard at Toms River to support the local militia. Signers included the village’s militia officers: Maj. John Cook, Capt. Samuel Bigelow, Lt. Joshua Studson, Capt. Andrew Brown, and Lt. Ephraim Jenkins, as well as the village magistrate, Abiel Aiken.

Loyalist Actions on the Shore

In May, the Loyalist partisan, James Moody, landed in Stafford Township, a year after co-leading a raid that razed the village of Tinton Falls 30 miles to the north. He was hoping to cross the state and kidnap Governor Livingston. The plot was never executed, but Moody spent several days on the shore in safety. Moody would later write that he "was obliged to put his life in the hands of the Loyalists” and “was never disappointed by any of them."

Three other Loyalist partisans entered New Jersey’s interior through the Monmouth shoreline. The New York Packet reported that on June 19:

Three spies [William Hutchinson, John Clawson, Lewis Lacey] and horse thieves were hanged at Headquarters near Morristown; they were taken in Monmouth County by some of our militia. The gang consisted of five, one was killed, and another made his escape. They were harbored by a Quaker, who is now in custody.

To the north, the stretches of the Shrewsbury Township shore were similarly in the hands of the disaffected. On September 30, Daniel Hendrickson, commanding the Shrewsbury militia, petitioned the New Jersey Assembly:

Setting forth that neither taxes nor militia fines can be collected in some places within limits of his regiment, by reason of the contiguity with the lines of the enemy, and praying that provision be made by the Legislature for furnishing officers appointed to collect taxes or militia fines with a guard for their protection.

The Assembly ordered Hendrickson to call out his regiment to protect the tax and fine collectors. One of Hendrickson’s militiamen, twice fined for delinquency, was Jesse Havens. He was indicted by the New Jersey Supreme Court three times in 1780. Two of the indictments were for trading illegally with New York, the third was because he "voluntarily and maliciously” did “harbor, counsel and feed a certain James Owens, Noah Morris, John Barton, Benjamin Lewis, knowing these to be enemies of the United States."

The disaffection of the Monmouth shore neighborhoods is discussed in a handful of Revolutionary War veteran’s pension applications as well. For example, John McBride, who served in Pulaski’s Legion when it was harassed in its march through Stafford Township in October 1778, recalled serving at Cedar Creek (at the southern tip of Monmouth County) "where there were many Tories and disaffected” in 1780. He "marched down to Cedar Bridge in search of Col. Tye who had a party of Negroes and runaways under him and were plundering the inhabitants." The reference to Tye is wrong but there was a mixed-race Pine Robber gang in the area led by William Davenport—it clashed with militia at Forked River in 1782.

John Thomas of Egg Harbor noted the difficulty of serving along the shore, “the country along the sea coast at that time was so thinly inhabited that when the militia were away the whole country was left almost defenceless.” Thomas noted that the prizes of American privateers attracted British and Loyalist counter-attacks, supported by local Loyalists:

They frequently landed from their boats and burnt the houses of men who were active in the Revolution, stole their cattle and sheep, burnt their hay barns &c and committed other depredations upon the property along Shore. The Refugees had become very troublesome also.

In 1781, Pine Robber gangs led by Wiliam Davenport and John Bacon dominated stretches of the lower Monmouth shore with the assistance of disaffected residents. They were economically tied to the British in New York who paid specie for lumber and foodstuffs brought from New Jersey. Historian Harry Ward noted that these same neighborhoods operated "a sort of underground railroad" for British and German prisoners escaping to New York.

In April 1782, however, following the hanging of Monmouth County’s Joshua Huddy, the British drydocked the Loyalist vessels that were the connective tissue between New York and the disaffected stretches of the shore. With their shipping cut off, some shore neighborhoods quickly fell in line. In May, Colonel David Forman wrote of his trip down the formerly dangerous Shrewsbury shoreline:

Yesterday, I was all through Shrewsbury - so great a change I never saw - the struggle now is who shall tender the greatest submission. The Tories of that country absolutely give up every idea of continuance of the war - they go so far as to expect an immediate withdrawing of all the [British] troops from New York.

Whether these shore residents were true Tories, as Forman suggested, or merely trimmers, who now trimmed their sails to the Continental cause, is an open question.

Related Historic Site: New Jersey Maritime Museum

Sources: Andrew Brown to Asher Holmes in David Fowler, Egregious Villains, Wood Rangers, and London Traders (Ph.D. Dissertation: Rutgers University, 1987) p 191; Andrew Brown to Asher Holmes, Monmouth County Historical Association, Cherry Hall Papers, box 5, folder 9; William Franklin’s quote is in Thomas Fleming, The Forgotten Victory: The Battle for New Jersey - 1780 (New York: Reader's Digest Press, 1973) p 30; William Smith, Historical Memoirs of William Smith: From 26 August 1778 to 12 November 1783 (New York: Arno, 1971) p 93; William Burke to John Jay, National Archives, Papers of the Continental Congress, M247, I78, Misc Letters to Congress, v 3, p 407; Zuriel Waterman, Rhode Islanders Record the Revolution: the Journals of William Humphrey and Zuriel Waterman (Providence: Rhode Island Publications Society, 1984) pp. 73-7; Elliott’s letter is in B. F. Stevens, ed., Facsimiles of Manuscripts in European Archives Relating to America, 1773–1783, [25 vols., London, 1889–1898], vol. 1, #115; Patrick Ferguson to Henry Clinton, Clements Library, U Michigan, Henry Clinton Papers, November 15, 1779; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 4, p 251; New York Gazette & Weekly Mercury, March 27, 1780; James Moody, Lieut. James Moody's Narrative of His Exertions and Sufferings in the Cause of Government, Since the Year 1776 (Gale - ECCO, 2010) pp. 13-4, 53-4; Theodore Sedgwick, Memoir of William Livingston (New York: J & J Harper, 1833) p 231; New York Packet article printed in William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 407; William Nelson, Austin Scott, et al., ed., New Jersey Archives (Newark, Somerville, and Trenton, New Jersey: 1901-1917) vol. 4, p 465; Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application of William McBride of NJ, National Archives, p3-4, 20-2; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, September 30, 1780, p 279; Petition, Monmouth County Historical Association, Haskell Collection, box 1, folder 22; New Jersey State Archives, Supreme Court Records, #35907; National Archives, John Thomas, R.10501, State of New Jersey, Gloucester County; Harry Ward, Between the Lines, (Westport, CT: Preager, 2002) pp. 110-1; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, John McBride of Middlesex Co, www.fold3.com/image/#26202858; Samuel Forman to William Livingston, New Jersey State Archives, William Livingston Papers, reel 14, May 20, 1781; Samuel Forman to William Livingston, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 4, p 326; Stafford petition is in Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 4, pp. 328, 356 note; David Forman to Elias Boudinot, Pennsylvania History Society, Gratz Collection, case 1, box 21, Nathaniel Scudder.