Militia from Other Counties Ordered into Monmouth

by Michael Adelberg

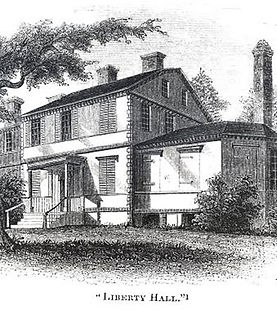

From his home, Liberty Hall, Gov. William Livingston considered Monmouth County’s security. Between 1779-1781, he often called up militia from other counties to march to Monmouth’s defense.

- January 1779 -

As noted in a prior article, ongoing pleas for assistance from Governor William Livingston and other New Jersey leaders through 1778 finally convinced George Washington to send a sizable body of troops into Monmouth County in January 1779. This led to a succession of regiments going into the county in the first half of 1779, under colonels Caleb North, Mordecai Gist, and Benjamin Ford.

New Jersey militia from other counties had come into Monmouth County on a few occasions prior to this. These early deployments are detailed in an appendix to this article. But, in January 1779, just as George Washington was determining that Continental troops had to be sent into Monmouth County, the New Jersey government was reaching the same conclusion about sending militia from other counties into Monmouth County.

Sending Militia from Other Counties in Monmouth County in 1779

On January 15, 1779, the Legislature’s upper house, the Legislative Council, called on Governor Livingston:

The Council advises his Excellency to call two classes of the militia from Burlington, one class from Hunterdon, one class from Middlesex and one class from the militia of Monmouth County, to be stationed under the command and in such parts of Monmouth County as Colonel Asher Holmes shall think best.

The same day, Livingston wrote Colonel Asher Holmes, leading Monmouth County’s largest militia regiment: “Having been unsuccessful in my applications to General Washington for some Continental troops to relieve your militia," he would call out militia from Middlesex, Hunterdon and Burlington "to be stationed under your command & in such parts of Monmouth County as you shall think best."

In response to this order, Burlington militia entered southern Monmouth County. Private John Jones of the Burlington Militia was killed in a skirmish with Pine Robbers at Cedar Creek Bridge, at the southern tip of Monmouth County, in February 1779. Militia turnout beyond this company of Burlington militia was apparently minimal.

On March 1, Governor William Livingston wrote the colonels of the Burlington, Hunterdon and Middlesex Militia to chastise them for the weak response to the January order:

I find by the return of men who came ordered as a guard for the County of Monmouth by my letter of the 15th of January last, so great a deficiency in the compliment required as really reflects disgrace on the Country. I hope that in procuring the relief [militia companies], your utmost efforts will be exerted, that whatever disgrace may be due the men for their backwardness in assisting a neighboring County more perilously exposed to the enemy.

Militia from the same counties were again called out to report to Asher Holmes in Monmouth County. Some Middlesex County responded to Livingston’s second order. Dennis McCormick of that county recalled serving at Long Branch in spring 1779 while other men from his regiment went to Elizabethtown: “the regiment to which he belonged was divided, a part was at Long Branch on the sea shore and the part to which he belonged was at Elizabethtown."

It is unclear if any other militia responded to the call. But it is clear that there was no short-term punishment for ignoring orders. At least one Middlesex Company refused to march into Monmouth County in February 1779. Middlesex County court martial records reveal that four officers were cashiered, including: "Lieutenant David Galliard of Col Scudder's Regiment, for disobeying orders, in not marching with Captain Perrine for the relief of Captain Stout, when stationed in Monmouth, February 1779." However, these court martials occurred more than two years after the fact—in March 1781.

On May 1, a frustrated Governor Livingston wrote General Washington about the poor turnout. He blamed insufficient patriotism, low wages, and weak fines for skipping service. He wrote that without better pay and stiffer fines “they [militia] will not come out to any purpose in monthly service." That same day, the Council voted to raise militia wages and directed the Governor to call out nine militia companies to guard shores of Bergen, Essex, Middlesex and Monmouth—facing British-held New York. On May 25, the Council received a report on militia deployments. It was noted that militia companies from Gloucester, Cumberland, and Salem counties had arrived in Monmouth County.

However, those militia companies did not stay long. On June 7, Livingston ordered those companies north to Elizabethtown in response to a threatened British attack. With the defenses of Monmouth County again weakened, Loyalists attacked the village Tinton Falls, the Whig outpost closest to Sandy Hook on June 10. They burned the village and captured all of its senior militia officers. The New Jersey Assembly responded by passing an act to raise 1,000 State Troops for six months continuous service. One of the two regiments would be stationed in Monmouth County under Colonel Holmes.

By any measure, the attempts to defend Monmouth County in 1779 with militia from other counties were disappointing. Few militia answered the call, and some of those that did were quickly transferred elsewhere. Efforts to protect Monmouth County with Continental troops were also generally unsuccessful. Monmouth County remained vulnerable to external raiders and internal Loyalist gangs.

Later Calls for Militia Assistance

On December 23, 1779, Governor Livingston called out 60 militia from Hunterdon and Burlington to join Monmouth militia in defending the county. He wrote Asher Holmes that the militia would "be stationed as a guard under your command in said County of Monmouth, for the defense of the frontiers thereof.” The results were again disappointing. On March 10, Holmes wrote Livingston stating that his letters to the colonels of those counties "have not received any answer of them, neither has a man from either county come to our assistance.” Holmes continued:

The full quota of our county has been on duty since the receipt of the order, which is the only men we have to guard our frontiers, which is a very extensive one, and in no degree equal to the task. The men are almost all worn out with the hard duty and inhabitants very uneasy as they daily expect a visit from the enemy, and have earnestly requested me to let your Excellency know of our defenseless situation.

Livingston tried again. He wrote a new order to the colonels of the Hunterdon, Burlington and Middlesex militias on March 18 ordering out one class from each county for Monmouth County. He further wrote:

If the calling out of one class does not produce thirty men, you are to call on a second and so on till the number is completed. Tho' the last call on your county proved totally ineffectual and not a single man was sent in to assist in defending a county exposed to the incursions of the enemy, it is expected that this call will meet with a punctual compliance, especially as the wages of both officers and men, as well as fines for disobeyance, are lately increased.

That same day, the New Jersey Assembly voted to triple the size of fines for militia delinquency.

It is unknown if militia answered the call, but on May 19, the New Jersey Legislature received a new petition from Monmouth County requesting "a number of militia to guard the frontiers of said county." The Council advised Governor Livingston "to order out forty men from each regiment of militia in the county of Burlington and thirty from each Regiment in Hunterdon, and eighty men from each regiment in the militia of Monmouth; to be relieved by a like number from the counties of Gloucester, Salem and Cumberland." The men would be placed under the command of Asher Holmes.

Two months later, on July 17, Governor Livingston wrote every New Jersey militia colonel calling out one company of militia to rally at Morristown and support the Continental Army in resisting a British incursion. Colonel Samuel Forman of Upper Freehold, who was responsible for guarding Monmouth County’s lower shore, requested to be excused. He sent the Governor a petition noting the vulnerable state of the Monmouth shore and a personal letter on the county’s continued troubles. He wrote:

It is not possible for the inhabitants of this county to prevent the frequent ravages of the enemy. They have been in Shrewsbury twice since the petition. They followed the rear of my scout, not exceeding a half hour's march. I wish the Governor and Privy Council may give what orders they think proper, but 500 men will not be equal to the task. In two skirmishes last week, our men retook the horses of the Enemy took from the neighborhood of Monmouth Court House and wounded one Negro. Yesterday, the enemy got their plunder: lost one man killed.

Livingston granted Forman’s request.

On October 7, the New Jersey Legislature again called on Governor Livingston to call out 150 militia from nearby counties "for the defense of the frontiers of the County of Monmouth.” The order acknowledged that militia “has not been furnished to that service, whereby the inhabitants of that quarter have been greatly exposed & harassed by parties of the enemy." Two months later, David Brearley of Upper Freehold, while serving as Chief Justice of the state’s Supreme Court asked Governor Livingston to send another company to guard the Monmouth County jail at Freehold because:

We received information last Sunday that a party of refugees was over, to the amount of thirty, but could not learn their designs. Yesterday we were informed that they were within a few miles of us, lying in the edge of the pines just south of this place, sixteen of them have been seen in a body from which I was led to believe that the court and prisoners in gaol were their object... I ordered the guard to be increased to fifty men, so that if they should attempt anything, I hope we shall be able to give a good account of them.

Livingston called out a company of Burlington militia. Orders to assist Monmouth County continued.

The Middlesex County Militia Refuses to Help

In 1781, the near-constant requests for help from Monmouth County produced pushback. On February 21, 1781, Colonel William Scudder of the Middlesex County militia (and brother of Nathaniel Scudder, Monmouth’s most prominent political leader) complained about the continual assignments in Monmouth County. He said his men are "conceiving themselves injured by being obliged to do the duty of other counties" and he called for "a more equitable plan for calling out the militia."

Four Middlesex County veterans pensioners recalled service in Monmouth County in the latter years of the war. Catherine Ashton, widow of Isaac Ashton, wrote of her husband’s service in the summer of 1780 to patrol “along the Amboy and Monmouth shore.” Samuel Grove recalled that in spring 1781 he “served another tour of one month in Monmouth County, where the Tories, Negroes and regular British & Hessians were making terrible ravages.” James Abraham recalled that in June 1781 he was "marched to Middletown in the county of Monmouth at the time the British, near 1500 strong, was out on tour one week." James McGee recalled in early 1782 marching with 31 men "as far along the shore as Middletown where the refugees were murdering and plundering the farmers."

Fatigue in the Middlesex County militia from marching into Monmouth County climaxed on March 21, 1781. On that day, at “the Battle of the 1500”, more than one thousand British regulars and Loyalists landed near Middletown and marched inland to Pleasant Valley. They gathered up dozens of livestock and took a few prisoners. The Monmouth militia hung on their flanks and skirmished with the massive raiding party, but lacked the strength to resist. The Middlesex militia at Cranbury heard of the raid and refused to help. On June 22, Captain Beatty at Cranbury informed Governor Livingston:

We have reason to believe the accounts [from Middletown] coming to this place are untrue… the militia of Monmouth County have been discharged from the field alarms - No fact is fixed however on the authenticity of this report: Col Scudder [of the Middlesex Militia] has thought fit to detain his regiment at this place.

Scudder did, however, send a mounted party to Englishtown “to gather more certain intelligence." This prompted a second report that day stating that "Genl. Arnold [Benedict Arnold] has entered Monmouth County with 3,500 men" – which greatly overstated the size of the attack. Citing the dangers of engaging such a fearsome attack, the Cranbury militia again stayed put. Meanwhile, Middlesex militia at Cheesequake (bordering Middletown) did join the fight.

Other Militia Activity

Beyond the Middlesex militia, Cumberland County militia served in Monmouth County in 1781. John Eldridge of Middletown recalled being sent to a Captain Woods who "had been sent from Cumberland County to relieve in some measure the militia of this County and were totally strangers to this applicant. Besides being a soldier, was a guide to the same." One of these militiamen, Benjamin Smith, recalled being stationed “at Toms River about 30 or 40 miles from Monmouth Court House.” Smith stayed in Monmouth County after his service was up. In 1782, he participated in a campaign against Pine Robbers “where they captured and hung a number of Tories.”

Parallel to militia from other counties being stationed in Monmouth County, militiamen put to sea as privateers to take British/Loyalist ships off the Monmouth shore. As early as January 1776, Essex County militia sailed around Sandy Hook to take the stranded British supply ship, Blue Mountain Valley; Middlesex County privateers, including New Jersey’s greatest privateer, Adam Hyler, successfully attacked British/Loyalist assets around Sandy Hook more than a dozen times. Militia boats from Cape May and Gloucester County battled London Traders and Pine Robbers off the Monmouth shoreline throughout the second half of the war.

Also later in the war, militia from Burlington and Gloucester came into Monmouth County for short periods of time in response to Loyalist provocations. The Burlington County militia pursued the Pine Robber gang of John Bacon at least three times. Two militiamen recalled marching north to March 1782 in response to the Loyalist attack on Toms River. John Peters recalled marching to “Toms River in Monmouth County in protecting the inhabitants against the depredations of the refugees.” Enoch Young recalled that, “He marched through the counties of Gloucester and Burlington and Monmouth to Toms River, at the Block House, to assist against the enemy in the engagement there, but was too late, the enemy had fled before they arrived.”

Loyalist raids into Monmouth County continued into spring 1782 and Pine Robber gangs operated with impunity along stretches of the shore into 1783. But there is no evidence that militia from other counties were assigned to Monmouth County after 1781. While militia from other counties were, at times, helpful to the security of Monmouth County, more often, they were less than that.

Related Historical Site: New Jersey National Guard Museum

Appendix: Militia from Other Counties in Monmouth County Prior to 1779

Twice in 1776, in July and again in November, Colonel Charles Read led Burlington County militia into Monmouth County to quell Loyalist insurrections. In the first action, it appears Read’s men did little beyond arresting a few prominent Loyalists in adjacent Upper Freehold township; in the second action, Read’s men went all the way to the Atlantic shore near Shrewsbury, and arrested dozens of men affiliated with Samuel Wright’s Loyalist association.

Just two months later, in January 1777, companies of Cumberland and Gloucester County militia entered the county and cooperated with Francis Gurney’s Pennsylvanians to topple the Loyalist insurrections. The service of the Cumberland County company was apparently considerable, as their commander, Major John Davis (along with Gurney), was publicly thanked by Monmouth County’s Nathaniel Scudder in a letter printed in the Pennsylvania Gazette on February 5:

To Major John Davis of the Cumberland County Militia, I am happy in this opportunity of presenting my compliments… In short, those detachments have rescued the county from the tyranny of the Tories and put it in the power of their own militia to recover and embody themselves in such a manner as to be able to stand on their own defence.

Interestingly, Scudder alluded to some disorder among the Cumberland militia. He gently chided Davis and Gurney to “correct and make amends to the utmost of your powers for those irregularities and errors which are the unavoidable consequences of a march of a detachment of militia in haste as you did, through a country where so many of the inhabitants were inimical to the cause.” The New Jersey militia detachments, while skirmishing and scattering Loyalists in the middle of winter, suffered at least two casualties. Captain McFarland of Cumberland County died at Freehold in February and Private James Malloy of Gloucester County died in a skirmish at Shrewsbury in March.

Militia from Middlesex and Cumberland counties returned to Monmouth County in early 1778 and were detached along the shore. William Lloyd joined a Middlesex County company under Captain Nixon "in pursuit of the Refugees of the Pines… [who] broke into the house of a man I knew and killed the man and his wife." Lloyd further noted:

[They] secreted themselves in the adjacent pines in the daytime and would come out at night to steal horses (and take them to the British by way of Sandy Hook) and rob the houses of the inhabitants of the neighborhood where they lived.

At this time, Armon Davis of Cumberland County was killed in a skirmish in Shrewsbury Township.

Roughly one thousand New Jersey Militia from several counties embodied under General Philemon Dickinson and entered Monmouth County immediately prior to the Battle of Monmouth. They played a supporting role in the battle, and melted away (greatly to Dickinson’s disappointment) shortly after the battle. A month later, the New Jersey government again considered ordering militia into Monmouth County on the first reports on Pine Robber gangs in county. On August 10, 1778, the legislature’s upper house, the Council, called on Governor Livingston to "order out one class of militia from each of the counties of Burlington and Monmouth, to be stationed in Monmouth as Colonel Asher Holmes shall think proper for securing the inhabitants and their property from the enemy and the disaffected persons skulking in the pines." It is not clear if Burlington militia arrived in the county.

As discussed earlier in this article, January 1779 was a tipping point in ordering militia from other counties for long term deployment into Monmouth County.

Sources: Pennsylvania Gazette, February 17, 1777 (CD-ROM at the David Library, #23302); Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 1, p 294; Munn, David, Battles and Skirmishes of the American Revolution in New Jersey, (Trenton: Bureau of Geology and Topography, New Jersey Geological Survey, 1976) p 43; John C. Dann, The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980) pp 135-16; David C. Munn, comp., Battles and Skirmishes of the American Revolution in New Jersey (Trenton, N.J.: Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Geology, 1976) pp. 95-7; David Bernstein, Minutes of the Governor's Privy Council, 1777-1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Library, Archives and History Bureau, 1974) p 83-4; David Bernstein, Minutes of the Governor's Privy Council, 1777-1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Library, Archives and History Bureau, 1974) p 112-3; William Livingston to Asher Holmes, New Jersey State Archives, William Livingston Papers, reel 9, January 15, 1779; Munn, David, Battles and Skirmishes of the American Revolution in New Jersey, (Trenton: Bureau of Geology and Topography, New Jersey Geological Survey, 1976) p 135; William Livingston to Burlington, Hunterdon and Middlesex Miliia Colonels, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 3, p 41; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Dennis McCormick of Middlesex Co, www.fold3.com/image/#24210668; William Livingston to George Washington, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 3, pp. 79-80; David Bernstein, Minutes of the Governor's Privy Council, 1777-1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Library, Archives and History Bureau, 1974) p 116-7; Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 3, pp. 99, 106-7, 112; New Jersey State Archives, William Livingston Papers, reel 10, December 23, 1779 and March 10, 1780; William Livingston to Militia Colonels, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 3, pp. 339-40; William Livingston to Asher Hollmes, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 3, pp. 326-7; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, May 13 and May 20, 1780, p 187-195; David Bernstein, Minutes of the Governor's Privy Council, 1777-1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Library, Archives and History Bureau, 1974) p 149; Samuel Forman to William Livingston, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 4, pp. 12, 28-9; Journals of the Legislative Council of New Jersey (Isaac Collins: State of New Jersey, 1780) p124; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, October 4 and 7, 1780, p 2293-298; David Fowler, Egregious Villains, Wood Rangers, and London Traders (Ph.D. Dissertation: Rutgers University, 1987) p 243; David Bearley to William Livingston, New Jersey State Archives, William Livingston Papers, reel 13, December 26, 1780; William Scudder to William Livingston, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 4, p 148; Militia Court Martial documents, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 4, p 162; Thomas Beatty to William Livingston, New Jersey State Archives, William Livingston Papers, reel 15, June 22, 1781; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Enoch Young of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/# 24155756; National Archives, Revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - John Eldridge; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Benjamin Smith of NY, www.fold3.com/image/# 16808699.